From the Trace: Art as a Space for the Transformation of Experience

Public discussion within the framework of the exhibition 7±2 by the residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier, led by artist Hanna Zubkova.

Group exhibition 7±2 by the residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier led by artist Hanna Zubkova

Assembly Hall of Fabrika, June 4–18, 2025

photo Tatyana Sushenkova

What does it mean to “research” in art? How do the mechanisms of transformation function—from the artist’s everyday experience into a work of art, from the artwork into a gaze, from the gaze into reflection, and from reflection back into everyday life?

Speakers:

Curator Liza Zemskova, artists Aruna Radha, Olga Shamshura, Yulia Kolganova, Olesya Gumenenko, Oksana Vinogradova, Oksana Timchenko, Viktoria Vysotskaya, philosopher Alexandra Volodina, critic Anastasia Khaustova

Moderator: Hanna Zubkova

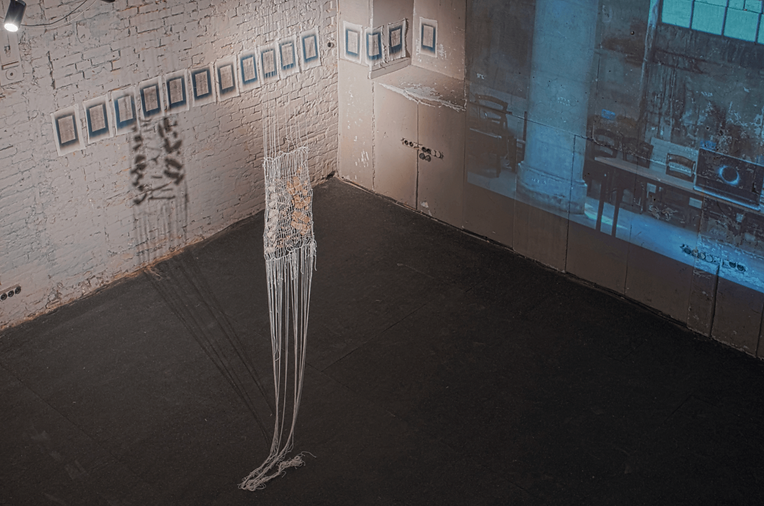

Group exhibition “7±2”

Residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier led by artist Hanna Zubkova

Assembly Hall of the "Fabrika" Center for Creative Industries, June 4–18, 2025

Hanna Zubkova: I’m pleased to welcome you to this public meeting held within the exhibition Seven Plus or Minus Two, featuring the residents of my Research Praxis Space workshop, here in the assembly hall of Fabrika and online.

Today I will briefly speak about the workshop, then outline some of the key thoughts for this meeting and introduce the exhibition. After that, I’ll pass the word to curator Liza Zemskova and the participating artists. Responding to their presentations, we’ll hear reflections from philosopher Alexandra Volodina and critic Anastasia Khaustova, to whom we are very grateful for joining us.

Group exhibition 7±2 by the residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier led by artist Hanna Zubkova

Assembly Hall of Fabrika, June 4–18, 2025

photo Tatyana Sushenkova

Jannis Kounellis once said that he works with what comes to him. This, perhaps, is the central motif of the atelier. I would like to speak about this responsiveness. I approach research in art not as a linear path from idea to result, but as a process in which form itself becomes a way of thinking. What emerges does not always unfold in discursive logic—knowledge can manifest in the body, in the situation, or in the material.

In this sense, I return to Jacques Rancière. In The Ignorant Schoolmaster, he radically rethinks the very notion of authority in knowledge, questioning the idea that knowledge must necessarily come from someone who "knows more," someone who occupies an institutionally recognized position. And in The Politics of Aesthetics, he introduces a concept that is particularly important to me: the distribution of the sensible—the way in which it is determined what can be perceived, by whom, and in which quality.

This is especially significant to me in the artistic process, where knowledge is not so much transmitted as it emerges.

I have been developing the Research Praxis Space atelier since 2017, both autonomously and in collaboration with various institutions and venues across Russia and Europe: Betonsalon – center for art and research in Paris, the BBE School of Design, the Institute of Contemporary Art Baza, among others. Although the program primarily takes place online, a key moment is always the exhibition, where the following question arises: what does it actually mean to organize an encounter between a work and its viewer? In what ways can this encounter be perceived—as a document, as an event, as a mode of knowledge production, and as a space of co-presence?

The process within the atelier unfolds between two poles: theory and practice. But I increasingly find myself questioning whether these notions can still be thought of as opposites. Can theory really be separated from practice, especially when we are dealing with embodied, material, or affective knowledge—knowledge that resists articulation? And what does practice mean in a context where any artistic gesture is already embedded within systems of discourse, infrastructures and representation?

My aim is for the theoretical component not to impose a top-down framework, but rather to create conditions in which participants can position their inquiries at the intersection of disciplines—forming knots between philosophy, anthropology, media theory, feminist critique, and popular culture. What matters to me is not a linear narrative or a canonical view of art history, but rather how the ideas and gestures of artists resonate with one another, how incisions —points of intersection—emerge, and what kind of dialogue they enter into with historical, social, biographical, and political contexts: both those in which the works were originally created, and those in which we encounter them today.

The practical part of the atelier is dedicated to the formation of research material. I invite participants to immerse themselves in their own process—using tools often borrowed from the academic field, but transformed in accordance with an artistic logic. This may involve working with personal or institutional archives, conducting field research, engaging with artifacts, contexts or found objects.

Research practices are also at the core of my own artistic work. For instance, the installation False Sun. The Catcher, which I presented last year at Garage Museum. This large-scale multimedia piece (you can read more about it in interviews and articles) emerged and unfolded from a unplanned encounter with a personal archive of a Soviet philosopher. This archive was not meant for me, and I hadn’t been looking for it. It came to me unexpectedly, raising the question of how an artist makes that initial choice: from where to begin. The archive—a small folder of seemingly unrelated documents—was destined to disappear, left among discarded belongings after the previous tenants had moved out. What interests me—both in the workshop and in my own practice—is how something that appears useless, random, forgotten, or left on the margins can give rise to an artwork. What constitutes this field of emergence?

The curator, Liza Zemskova, will speak further about this and other questions raised by the exhibition 7±2. For me, the show took shape as a reflection on what an artist’s work is made of—how it comes into being not in isolation, but through interaction with other works and with the viewers themselves: how they feel, what they’re thinking in that moment, and even in relation to the limits defined by their own bodies.

Group exhibition 7±2 by the residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier led by artist Hanna Zubkova

Assembly Hall of Fabrika, June 4–18, 2025

photo Tatyana Sushenkova

The title Seven Plus or Minus Two refers to a cognitive principle that describes the capacity of short-term memory—how many objects a person can hold in their mind at once in a state ready for use. In other words, when you look at the next work in the exhibition, you may no longer remember the previous one, or it begins to refract through the new one, or project onto it.

And it’s this question—how an artwork emerges from the everyday life of the artist, through their reflection and individual process—that I would like to explore with you. How, then, within the exhibition, does the moment of encounter with the Other take place? And how does that Other, through their own process and reflection, return to everyday life with a newly formed experience?

This is a kind of arc of transformation that I proposed as a framework for our conversation—but we will see where it leads us. Each artist presenting today has their own way of turning the background of daily life into the figure of an artwork. Richard Serra created a work called Verb List, in which he compiled verbs that demand an action upon an object—such as to roll, to crumple, to fold, to store, to bend, to shorten, and so on. Serra viewed this list as a reflection of actions performed on material, space, and process.

In a similar spirit, we have arrived at a list of nouns—each one reflecting a particular mode of transformation embodied by each participant: adaptation, entwinement, reprocessing, glitch, naming, gazing, contact, montage, presence.

And now, I would like to hand the floor over to Liza, who will speak further about the exhibition’s overall concept and how the idea of transformation is articulated through its structure.

Liza Zemskova: Thank you. I believe we’re not speaking of transformation as a single, sudden event, but rather as an ongoing process that unfolds through relationships—between works, between artists, between viewers and space. In this sense, the exhibition 7±2 was conceived as an experiment: an attempt to create a situation in which these connections become visible—not frozen in one form, but moving, returning to themselves, and transforming.

Group exhibition 7±2 by the residents of the Research Praxis Space atelier led by artist Hanna Zubkova

Assembly Hall of Fabrika, June 4–18, 2025

photo Tatyana Sushenkova

"An experiment in creating recursion under contingent conditions of an exhibition" — this is an attempt to look at the relationships between objects, space, viewers, and other elements as a recursive system.

But what does that mean?

Recursion is when a system loops back onto itself in order to define, understand, or reconfigure its own boundaries. It’s a circular or spiral movement that doesn’t simply repeat what has already happened, but shifts slightly each time. It’s not a linear cause-and-effect logic, but an ongoing process of self-reference and transformation.

And crucially, this recursion is impossible without errors, glitches, or accidents—in other words, what philosophers refer to as contingency. In this sense, it was important for me not to eliminate unpredictability, but rather to invite it into the structure. As Yuk Hui writes, it is precisely contingency—the possibility of deviation from the expected—that makes a system alive and capable of development. It doesn’t obstruct; on the contrary, it triggers new loops of change, new strategies of adaptation.

Hui, here, is in dialogue with Quentin Meillassoux’s notion of “absolute contingency.” For Meillassoux, contingency exists as an abstract possibility for anything to happen. Hui, however, treats it as operative material—something that functions within systems capable of transformation. This logic becomes especially relevant when we think of an exhibition not as a fixed form, but as a processual structure in which every element—even a glitch—can become generative.

To me, this captures what we tried to do here. A work might suddenly interact with a neighboring one—not because they were pre-aligned, but because something third occurred in the moment. This principle can be applied not only to living systems, but also to technical ones. Both types of systems act recursively upon themselves: they affect and transform themselves and one another, constantly recalibrating in the process.

Sympoiesis—a term proposed by Donna Haraway—describes the co-existence, co-creation, and co-becoming of various forms of life and objects within a single system. It is a process in which the boundaries between participants are not predetermined but gradually emerge through mutual influence. Matter and knowledge do not exist separately or independently, but arise together, evolving through continuous interrelation and exchange. In this framework, the rigid division between subject and object is abolished: everything is in a state of becoming, where each element shapes the other and is itself transformed.

The works selected for the 7±2 exhibition invite such interaction—between each other, with the viewer, with the space, or within themselves—between their various components, whether through expressed ideas, narrative threads, performative protocols, or material embodiment.

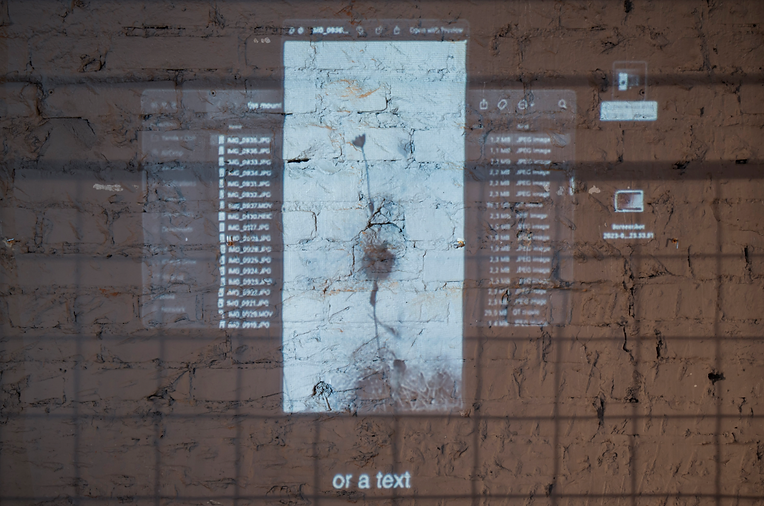

Hanna Zubkova: You’re also participating in the exhibition as an artist. It struck me that your work—despite the seriousness of your curatorial approach and philosophical references—is, in a way, an ironic commentary on your own idea.

On one hand, it attempts to reflect on what knowledge is, how we try to fix it in diagrams, structures, and systems, and where the limits of that fixation lie. But on the other hand, it’s a romantically ironic piece in which knowledge quite literally scatters in the wind—failing to form any stable system, and instead displaying absurd mutation, elusiveness, evanescence.

Liza Zemskova: My work, ironically titled Logos, draws attention to the chaos underlying a reality that can never be fully captured by its manifestations. The magic of scientific rituals brings us closer to that reality, but never truly touches it. There’s always an unreachable element—within the object or the subject—that guarantees the glitch, the error, the illusion of clarity.

The installation plays with tools of observation, description, and analysis. Tracing paper—a delicate, transparent material intended for technical drawings—exposes its own fragility, its ghost-like quality, and its inability to contain information within predefined systems, which fall apart at the slightest gust of air. The drawings, which reference diagrams and graphs, are deliberately absurd—as if the objects of documentation themselves resist being grasped, slipping away and mutating before our eyes. It’s a gesture of control that has gone out of control.

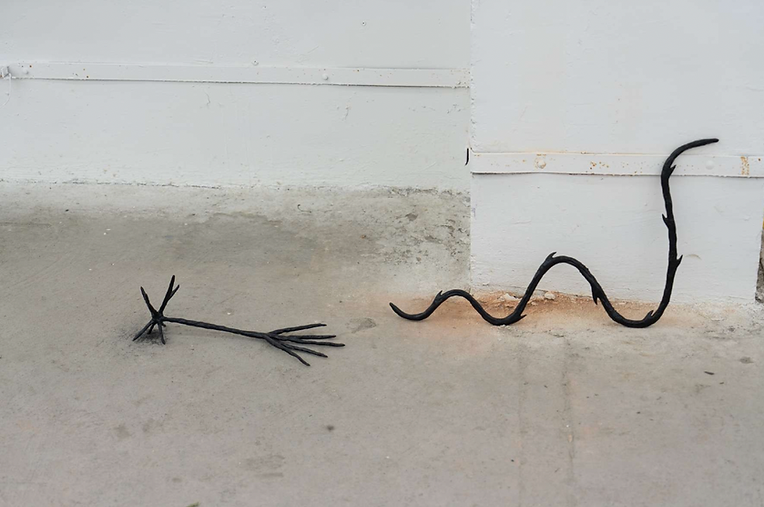

Hanna Zubkova: It’s a bit like the way you place objects in space. Liza, if I may, I’d like to recall one of your earlier works—Departure to the Moon, for example. That was an interesting case where the artist also took on a kind of curatorial role: the project was part of a group exhibition, but your work included several elements scattered across different zones of the space. They seemed to echo each other—some parts were traces, others events, and the viewer became a witness to a story, to a ruin, to something that had taken place before their arrival. I feel that experience has also shaped how you now choose and relate objects within this exhibition.

Liza Zemskova: Whether as a curator or as an artist, I’m constantly drawn to creating “scenes,” to unfolding the dramatic aspect of an exhibition. I’d like to take this even further—using more unpredictable and refined rhythms of impression, and a choreography of the viewer’s attention. I’m fascinated by the process of studying works and their contexts. I observed how my interpretations emerged and evolved—peeling away one layer of meaning after another—how shaping the physical dynamics breathes life into the space and temporality of the exhibition.

Hanna Zubkova: Thank you. Now I’ll hand the floor to Aruna Radha—one of the participants, who is currently in London. Today, I will act as her medium and speak on her behalf.

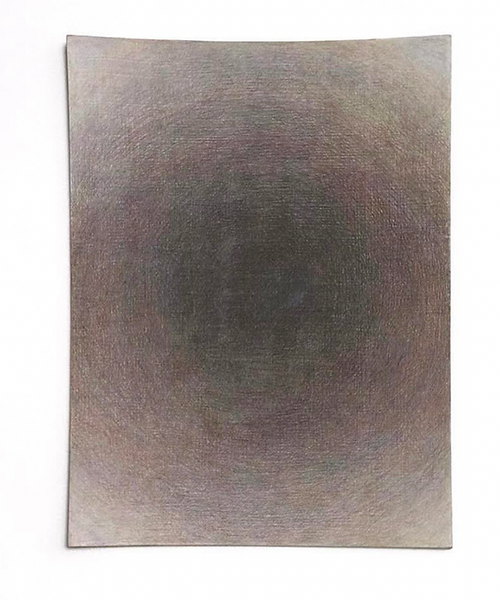

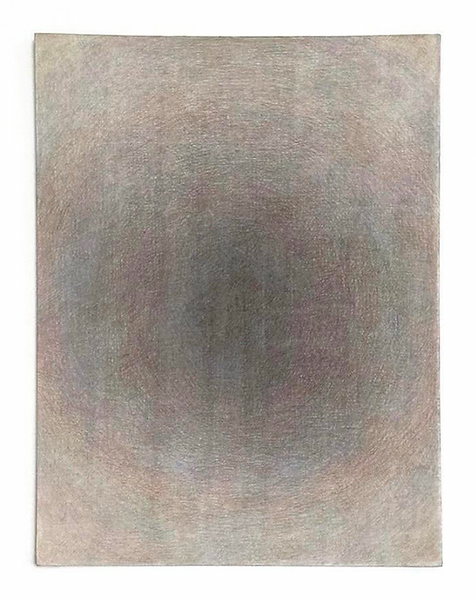

Her work continues the reflection on processes of adaptation—whether it be the adaptation of objects to each other, to the environment, or to the viewer’s gaze. It is a series of drawings, in which, from a distance, one can make out gray forms—perhaps bodies, or traces on a body. But when you come closer, something else happens: the artist invites the viewer into a performative interaction—asking them to take the sheets into their hands, to touch, to examine them. These are originals, not printed copies. This act of touching becomes an intended gesture, a gesture that activates the work. It gradually transforms it: the drawings may become deformed, damaged, bear traces. They were created from the outset with this contingency in mind—with an openness to chance and the influence of situation.

The grey here is not emptiness—not neutrality as absence. It’s the result of a blending of different colors. Each work has its own palette. This is how a form emerges that may appear “neutral” at first glance, but in fact contains a multitude of differences—differences that remain invisible from afar.

If you step closer and begin to examine the work, you’ll notice that it is not simply a representation of an object—because there is no object as such. The forms we see are negative silhouettes, shaped through an action: the artist randomly scatters sheets of paper and then meditatively traces around them, filling in the surrounding space. This process gives rise to both positive and negative zones.

But the most intriguing moment comes when you begin to truly look—when you immerse yourself in each mark, each line, each stroke. This act of looking creates a sense of deep engagement, a kind of absorption into the work. The drawing here is not just an image; it’s also a reflection on the medium itself: on drawing, on the color grey, on neutrality.

What is greyness? Where are its boundaries? What kind of autonomy does "the grey" possess—as a code, as a materiality?

In her practice, Aruna explores both experimental drawing and the themes it touches upon. For example, she has created a series of objects—convex and concave forms reminiscent of meditative bowls. Their surfaces are also covered with drawings, made in various colors that, when layered, produce grey. Through the play of volume and tone, these objects invite the viewer to look closely, to examine, to listen—into the material, into the greyness, into the silence.

And at some point—through an almost neurobiological process linked to the act of marking space—I felt an internal connection to Olya Shamshura’s work Dry Emotions.

Why neurobiological? Because at the core of this work lies the phenomenon of automatic drawing, where the act of drawing itself becomes a form of embodied release—a necessity to discharge inner tension in order to make space, within the body-mind, for routine, mundane, yet “necessary” activities. These drawings were made in the margins of daily planners—amid to-do lists, work schedules, and reminders. It’s in that movement, between the lines, that what Olya calls dry emotions begins to emerge.

I think there’s another important and complex theme here—one I often reflect on: how artistic production can be pushed to the periphery of so-called “real” life, especially if you are, for instance, a working woman, a mother, a person juggling multiple roles and obligations. This work reminds me that art, not as a project but as something bodily, uncontrollable, insists on making space for itself—literally in the margins of someone else’s agenda, amid errands and tasks—as a form of resistance to forgetting and inner deadening.

Olya Shamshura: As I moved from city to city, from one apartment to another, I noticed that I kept bringing my planners with me—those linked to specific periods of my life. After one of my recent moves, they ended up lying out in the open. There was no more space for them in my current life. But I couldn’t bring myself to throw them away. So I decided to start engaging with them.

After flipping through them multiple times, I realized that the way I perceived the information inside had changed. Meetings, business calls, phone numbers—they had all lost their original significance. The very reasons I kept those planners had completely faded. But the doodles in the margins—drawn through automatic writing, and once perceived as a mere byproduct—took on a new importance. As I looked closely at those hooks and scribbles, I began to recall the emotions I had felt at the moment they were made.

Olya Shamshura: As a result, I reworked most of the planners—transforming the written pages into new sheets of paper, onto which I placed the cut-out drawings. What was once the core became the background. What had been relegated to the margins came to the forefront—because it carried the imprints of emotions and states of being.

My work is about what we choose to carry with us.

Hanna Zubkova: One of your early works from 2021 was, in a way, what brought us together—since we’re both from Belarus and were deeply affected by the context of 2020. Maybe you could say a few words about your piece (Not) Bearing Pain?

Olya Shamshura: It consists of two elements: a wash drawing of a fracture in a hollow-core concrete slab, and a model of my childhood bedroom. In essence, I associate myself with that cracked concrete slab—one that could no longer withstand everything that’s happened since 2020.

Hanna Zubkova: It’s worth adding that the model you see on the right is an exact replica of your childhood room—in a typical post-Soviet apartment building, whose layout is repeated from flat to flat and likely exists not only in Belarus. This sense of impersonality—of what should be an intimate experience of interior space—suddenly gains its uniqueness precisely because it has been recreated by your hand, through your feeling, through your gesture.

I think this opens up a broader conversation about how the attempt to systematize memory, to lay it out into diagrams and give experience a legible form, doesn’t always lead to clarity. We may say: this is memory. But maybe it’s not. And it’s precisely this potential gap between schema and experience, between recording and living, that Yulia Kolganova’s work Soft Diagram engages with. I now give the floor to her.

Yulia Kolganova: A bit about the context from which Soft Diagram emerged. I’ve been working at the Skolkovo School for 13 years. When I first started there, it quickly became clear that balancing an artistic practice with full-time work would be difficult. So I decided to use the institution itself as a site for observation and practice—an opportunity to explore the intersections between business and art.

Over time, I began to notice that the knowledge we generate and discuss within such educational environments is often difficult to absorb. It requires time and inner work. An artistic approach helps to shorten that distance, turning abstract ideas into more tangible forms. That’s how the idea came to me to apply artistic tools within a professional setting.

Yulia Kolganova: At the moment, I’m developing two projects. The first is an educational residency where artists and entrepreneurs try to create a visual image together—one that reflects shared thinking. What matters to me is that this is not just an exchange of roles, but an attempt to build a common language, in which neither side remains unchanged. The second project is closer to a classical artistic practice. I observe how a shared theme emerges within a learning group and translate it into an image. I search for a motif in the history of painting that resonates with the issue being discussed, sketch it, shift the perspective, invert it.

As for Soft Scheme, this work was created as a birthday gift for one of the School’s most intensive programs. In this educational environment, complex logical diagrams are frequently used—they appear on whiteboards as a way of explaining principles and then are erased, disappear.

The idea behind the gift was to preserve one of these diagrams and create a moment for reflection: what remains after the diagram? What does it conceal? What lies behind the educational process itself?

I quite literally “encased” the diagram, made it impossible to erase—fixed it as an object. At the same time, I added a load-bearing column, wrapped in hide. These two elements—the diagram and the hide—belong to different worlds, but their conjunction creates a tension between abstract knowledge and embodied presence.

The diagram seems to float in space, transformed into a heavy metal structure—and yet the title includes the word “soft.” This softness speaks to the distance between the diagram and the hide, to the attempt not just to understand the structure itself, but the process of connection—its contradictions and vulnerabilities.

Hanna Zubkova: What you call a soft scheme, to me, felt more like a critical response—a rethinking of the very approach you’re describing. An approach grounded in the belief that one can clearly map out the future. This diagram seems to call that certainty into question. It transports us into a space where it’s no longer clear what kind of future we’re speaking about, whether it can be designed at all, or whether it loses its meaning once it’s literally “locked in metal.”

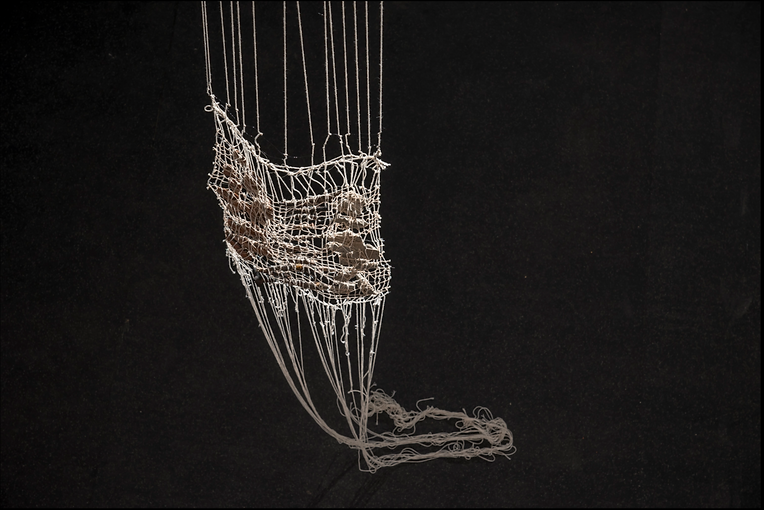

Hanna Zubkova, If Only I Could Be a Fisherman of Souls, 2019, fragment © Hanna Zubkova

Taken out of the context of business planning and management, the scheme here transforms into something more fragile, open and not entirely defined. It carries with it a sense of anxiety, uncertainty—it's unclear how to interact with it or what exactly it points to. Where the scheme offers a fragment of knowledge and simultaneously casts doubt upon it, Narcissus Trap, a work by Olesya Gumenenko, draws attention to how we perceive ourselves within the exhibition space—how we reflect, both literally and metaphorically, within a system we don’t always notice.

Olesya Gumenenko: I want to begin with a short story. At the opening, a friend of mine—an artist—asked: "Where is your work?" I replied, "It’s everywhere, it’s all around, it’s dispersed" A psychoanalyst might interpret this as a desire for perfection, for filling the entire space.

My work is titled Narcissus Trap. It consists of distributed mirrors scattered throughout the exhibition space, interwoven with other artistic projects. They have no frame, no center, no unified focus. They are not mirrors you can comfortably gaze into.

They are traps.

One day I found myself wondering why it’s so hard for a person to pass by a mirror without looking into it. And what happens if we scatter such traps between works of art?

When we look into a mirror, we always find ourselves on a kind of stage: we don’t just see ourselves—we recognize what we’re seeing. This double movement—gaze and recognition—produces the illusion of wholeness. Jacques Lacan described this in his theory of the mirror stage: the child, upon seeing their reflection for the first time, experiences the euphoria of a unified image—an image that doesn’t actually exist yet. From that moment on, the subject is permanently split: they live in a constant search for that ideal image, enamored with the reflection but never able to fully coincide with it.

This is narcissism in Lacan’s sense—not self-love, but a dependency on an impossible unity. Narcissus doesn’t long to be loved—he longs to be seen as whole.

Olesya Gumenenko: My work offers the viewer multiple mirrors—but the reflections are cut off, fragmented, intruding into other people’s fragments, into other people’s gestures. In this fractured space, admiration becomes impossible. I place the viewer in a situation where, in the moment of contemplating artworks, attention slips away. What appears to be a chance to look at oneself is disrupted—colliding with the other. This isn’t only about the image of the body, but also about the image of the artist, the viewer, the artwork itself.

At what point does the gaze become an act of admiration? At what point does admiration turn into blindness toward the other?

Hanna Zubkova: Would you tell us about your other projects? We’re seeing one of them here as well, and maybe there’s a connection between what you’re showing now and what you do more broadly.

Olesya Gumenenko: I think of art as a gesture—as an act that doesn’t necessarily speak, but always does. This gesture is not about expressing the self, but about creating a tension, a situation, a scene—where someone is looking, someone is seen, and no one controls the direction of that gaze.

As an artist, I search for ways to sustain this tension: between the desire to be seen and the fear of being visible.

Olesya Gumenenko: Narcissus Trap is not only about the mirrors themselves, but also about the very act of placing them within a space where the viewer is compelled to become a participant—but not the protagonist. It is a gesture in which I reject the central image in order to emphasize the impossibility of wholeness—in reflection, in perception, and in the very notion of the “self.”

Hanna Zubkova: Some of your works quite literally leave marks on the body—scars—like in the performance Counterload, and they raise the theme of limits—both physical and social. In Narcissus Trap, I found the idea of the peripheral gaze especially compelling. A gaze that isn’t directed straight ahead, but rather catches something out of the corner of the eye. When the artist’s work allows the viewer to see themselves from the side, so to speak—to begin observing and recognizing.

Hanna Zubkova: I think this is directly related to the theme of identity—how we look: at ourselves, at others, from the inside and from the outside. And in this context, I’d like to pass the floor to Oksana Timchenko, whose work Mountain seems not quite embedded within the exhibition space, but rather positioned just beyond its boundaries. Maybe you could tell us why that is?

Oksana Timchenko: I create texts, video works, and installations in the genre of autofiction. Taken together, my works form a heterogeneous archive—its fragments are interconnected and can offer different perspectives on the same topic, event, or character. For instance, a text might reconstruct and analyze an event in detail, or examine an image that emerges in the process of artistic practice. Meanwhile, a video essay or installation may be stripped of explicit themes and characters—something I’ve done when working with taboo topics such as HIV or suicide. The image is left open to interpretation by the viewer, and those interpretations may or may not intersect with my own experience.

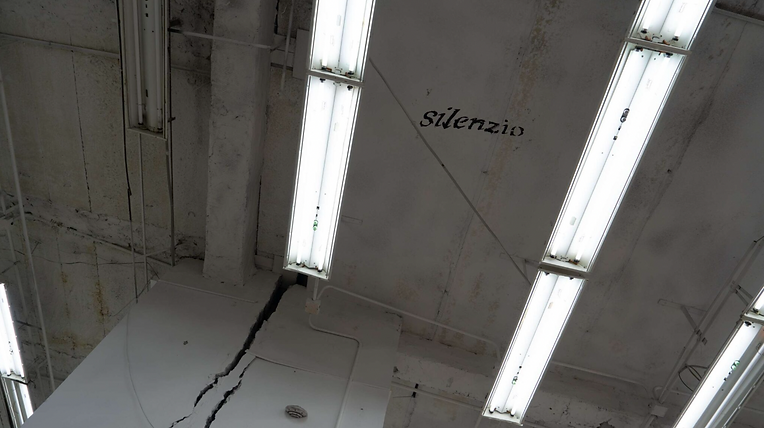

Oksana Timchenko: Speaking of Mountain, the work presented in this exhibition—it began to take shape when, shortly before the mobilization, I found myself in the mountains of Georgia and stayed there. That period was mostly made up of climbing the mountain and engaging in spontaneous artistic and research practices. The mountain is the only thing visible from my window, and I like to think of it as an object that shielded me—from the global context, from social ties, and even from personal and family history. In this sense, the mountain became a new boundary—one that allowed me to begin constructing a new identity, while my attention shifted toward objects of a different scale.

At the same time, anxiety and imagery associated with war are still present in the work. For instance, the photos of last year’s flowers breaking through the ice are a kind of remake of drone images of battlefields with the remains of soldiers. The footage of dogs, whose play resembles aggressive interaction, expresses my desire to renounce language—because words are imprecise, inadequate, frightening, or distorted by false intonations.

There is also a choreography element. It was born from the thought that, in such a time, I could only trust the mountain, rely solely on it—only it is unshakable. And I wanted to become it. The choreography records my attempt to align, even just with its outline.

But in the end, all of these themes can remain outside the viewer’s interpretation. The work may simply appear romantic and light.

Oksana Timchenko: As for editing—originally I worked with video and told stories in a linear fashion, though I always leaned toward non-narrative approaches. Mountain is my first attempt to bring editing into physical space—to extend the story into a bodily experience. This fragmentary montage, interrupted by chance, by mistakes, by intuitive actions—that’s how I think in general. It would be much harder for me to articulate what I want to say in text.

In montage, the material feels more flexible, more fluid. It also allows me to build a myth in place of lived experience—something that feels more truthful, even in the unstable language of images.

Hanna Zubkova: When Oksana Timchenko and I spoke about her work, what stayed with me was this desire to physically align with the mountain—literally, through bodily gesture and choreography. The mountain becomes a kind of figure of trust—the only thing one can lean on in a moment when words no longer work.

I find it interesting how this attention to space, to the body, to materiality, also resonates in the work of Oksana Vinogradova. Her work too includes a motif of return—to a place, to a landscape.

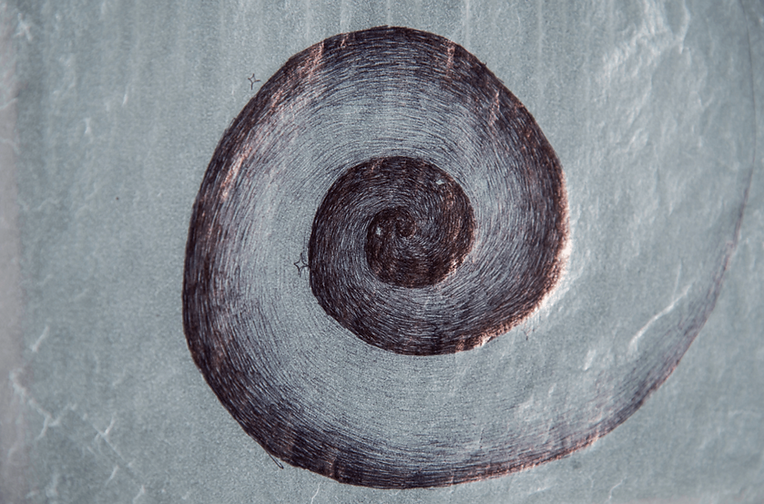

Oksana Vinogradova: My installation in this exhibition, Witnesses and Observers, emerged from a long-term engagement with the area around Lake Lisi in Tbilisi, where I lived for about two years. This landscape became not so much a subject as a material for observation, for recording, for doubt. I treated it as a fragmented field of traces—not immediately obvious, but slowly accumulating: through paths, fragments, and remnants of inhabitation.

I wouldn’t say I initially set out to create a work. It was more a way of practicing attention toward the space I was living in.

Returning again and again, I gradually began collecting fragments and shards: pieces of old slate, charcoal from campfires, nails, tree bark. At some point, all of it seemed to lose both its original function and its ontological distinctions—this used to be a house, that a tree, that a fire. It all collapsed into something singular.

What interested me in these found objects wasn’t their symbolic meaning, but their current state. Instead of striving for wholeness, I focused on stitching, joining, layering. Not resurrection, but the registration of change. In these fragments, there are traces of different types of presence: human, animal, temporal.

The vertical elements in the installation are both construction debris and insect movement patterns in bark. The horizontal connections are what hold the entire structure together—but they also point to the fact that this stability is only relative.

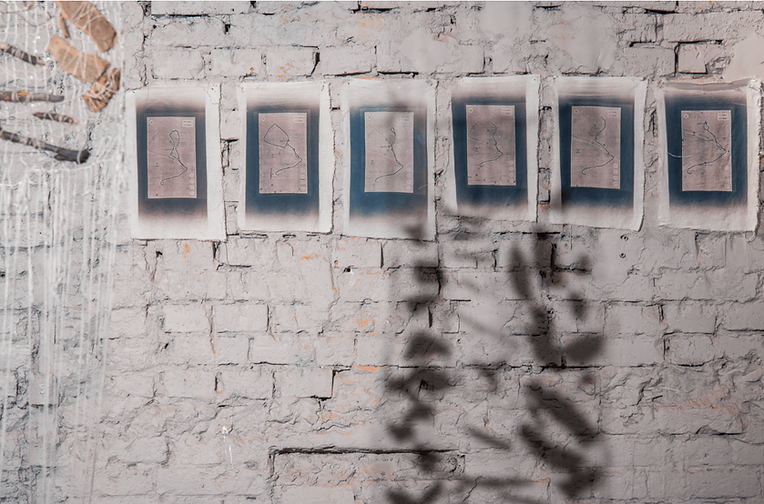

In addition, I recorded the routes of my walks with a GPS tracker. What emerged was a strange kind of drawing—a sort of signature, born out of repeated returns. These lines became the basis for a series of cyanotypes that, in a way, outline the “perimeter” of the entire work.

If we speak more broadly, it’s important for me to work with locality—not in the spirit of local identity or nostalgia, but rather as a process of immersion, of careful observation, of building personal relationships with space. My attention often shifts to details that might seem insignificant: repetitions, mistakes, glitches—the very “small things” that usually go unnoticed. I suppose, for me, this is a way of working with entropy. Not to overcome it, but to somehow meet it.

Hanna Zubkova: Oksana’s work touches on a theme that is central to the entire exhibition: how observation and return begin to form a kind of temporal structure. But a structure that is not fixed—it responds, it’s stitched together from fragile fragments that may seem incompatible. And I find it fascinating how this idea of structure as a situation, as a temporary assemblage, continues to resonate in the work of Vika Vysotskaya.

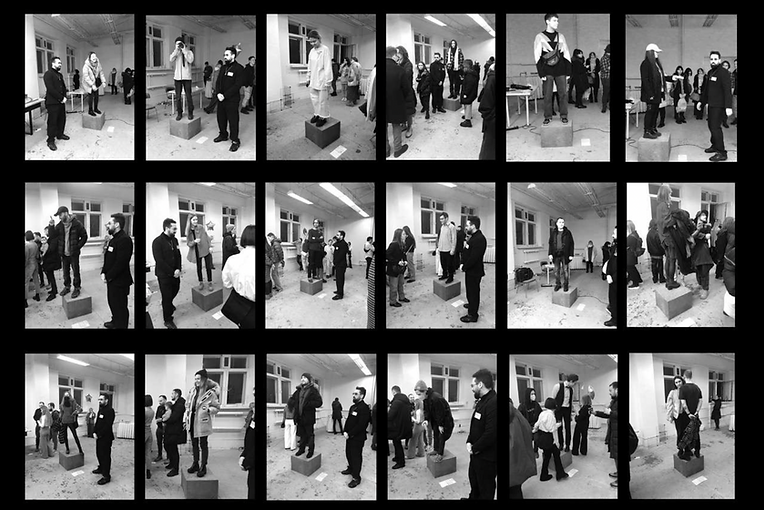

She lives in Berlin but is joining us online today. I’ll say a few words on her behalf—or perhaps not even me, but the object itself, which is here, at the center of the space.

The work is titled The Foundation of Power. It’s a performative object that appears in different locations and adapts each time to the space it finds itself in. For example, at Elektrozavod, the cube was a different color, mimicking the physical properties and appearance of its surroundings.

The idea is that at a certain moment, a person can step onto the cube. But they can only step down if they find a successor. Before leaving this "position," they must ensure it won’t remain vacant.

Viewers don’t always follow these rules—they do things their own way. And perhaps this is precisely where the question emerges: what is a performative object?

In some versions, Vika uses performers who accompany the process—guiding the score of transitions and designations. She works with performativity and communication, both within the physical exhibition space and beyond it. She recently initiated the project See Our Vision (SOV) in Berlin—a gallery, educational platform, and media space—and we hope that one of the next Research Praxis Space exhibitions will take place there.

What matters to me is that such exchanges continue—no matter what. Thanks to horizontal initiatives, which may not be marked on the major cultural maps, but which are precisely the ones that build meaningful connections: whether it’s my workshop Research Praxis Space, or new initiatives launched by current or former participants and residents. I sincerely hope that we will keep creating things together.

Now I’d like to pass the floor to our guests. Perhaps you’d like to share something that resonated with you, after everything you’ve heard today.

Alexandra Volodina: When Hanna and I discussed in advance how today’s conversation might unfold, we reflected in particular on the idea of translation—translating lived experience into artistic language, personal emotion into artwork, memory and past experience into images, forms, and materials.

A whole chain of associations came to mind, and perhaps one of the first and most persistent—though at first glance, a simple one—was the idea of the archive, which seems to me to run through many of the works presented today. The archive as a central thread in contemporary art and cultural theory.

On one hand, the archive is an attempt to fix reality, to make sense of it, to find schemes, images, or structures through which something can be preserved and transmitted. But on the other hand, an artistic archive is not the same as an archive in the classical sense—library, museum, institutional. The classical archive strives for transparency and order. It assumes that if something has been included in the archive, it must be important. And that which is excluded is deemed accidental, irrelevant. It lays claim to system, completeness, even authority over the material.

An artistic archive, by contrast, may be organized quite differently. It can be more free. It may not claim completeness at all. On the contrary, it may emphasize gaps, ruptures, emotional fluctuations. It can work with what doesn’t fit the framework—with what cannot be systematized. And it is in those cracks between systems, in the effort to express what slips away—that living life remains.

That was the first thread that emerged for me when I began engaging with the exhibition. But when I found myself in the space and listened to all of you, I began thinking more about the translation of environment into artistic form. About translating experience—into image, into emotion, into language, into the visual, into the sensory. And that brought to mind the idea of the trace.

The notion of the trace appears in both philosophy and linguistics—for example, in Jacques Derrida’s Of Grammatology. There, it’s treated as a rather complex structure. A trace is, on one hand, the imprint of something that has already happened—personal, social, historical, or political experiences that have left a mark on our lives. We then try to work with that imprint—to reflect on it, to make sense of it, to transform it.

But on the other hand, a trace is not only what’s left behind—it’s also what is manifesting right now. A trace is at once a remnant, a present event, and an image. Like when we notice that animals have passed through a place—their tracks contain both what has already happened and what we perceive now as movement, as trajectory, as a pattern existing here and now.

I feel that the metaphor of the trace beautifully captures what we’ve been discussing today—because it bridges process and result. It applies, among other things, to the very logic of how the workshop functions: on the one hand, there’s an emphasis on the process, on something still taking shape, still not fully fixed. On the other hand, there are already attempts to translate that experience into an artistic language.

A trace, in this sense, is what the artist leaves in the space between movement and fixation—between the living process and the finished image. And I think that aligns perfectly with the format of the workshop: a collective inquiry in which not only the outcome matters, but also the visibility of the path itself. As a viewer, you may not know all the details, but you feel—something has happened. You see the traces of that process. That becomes an entry point, it sparks interest. And from there, many lines of thought open up—things to reflect on, to discuss, to dive into.

For me personally, even though I participated asynchronously, this experience was very meaningful. I joined in gradually, a little later than others, but still felt included.

I’d also like to briefly mention another thread that emerged for me: the distinction between figure and ground. I started thinking about it when I encountered one of the works, though of course it may be relevant to others as well.

The figure is usually what sits at the center of the image—what draws the eye. The ground is the context in which the figure emerges—what at first glance appears secondary. But in fact, the background speaks no less. It provides the context, the conditions under which the work is created. It absorbs social and cultural codes. And if we look more closely, it becomes clear that the background is not empty space. It’s what supports and shapes the figure—and often reveals more than the central image itself.

The distribution and positioning—of figure and ground, of subject and the environment in which they’re embedded—are never straightforward. And I think the performative project we discussed today brings this tension to the surface. It may be a general idea, but each time we approach it, it unfolds in new ways.

In the case of Vika Vysotskaya’s cube, this inquiry takes shape through the theme of power—even if approached in a playful mode. But it’s precisely through play that something becomes clear: how a simple mechanism of power distribution can pull someone out of the background, out of the environment, and make that person the figure, the center—and then demand that they pass that function on to someone else. I find that a very precise and insightful observation.

This brought to mind the concept of affordance—often discussed in the context of human interaction with objects, especially in design, but also in a broader cultural sense. Affordance refers to the ability of an object or environment to “offer” certain actions—possibilities of use that we recognize based on our own bodily and cognitive capacities. For example, a step “invites” us to climb it—but only if we are upright beings with enough strength to lift ourselves. Or a door handle, which seems to say: “pull,” “turn.”

There are also environments that are saturated with affordances—dense with potential for interaction. I even recalled the phrase dense environment—something that can be read in multiple ways, used in multiple ways. But not every element of an environment is perceived as an affordance. Some are proto-affordances—we don’t yet know how to recognize them.

And in this, I think, lies one of the tasks of art: to reveal in what seemed insignificant, secondary, or background—a possibility. A possibility for new action, new meaning, new ways of seeing. For me, this is one of the central threads running through many of the works presented today.

Thank you again for the opportunity to be part of this shared space—to listen, observe, and think together.

Hanna Zubkova: Thank you so much. I feel that this perspective you’ve offered through the concept of affordance opens up a new dimension—especially in connection with your own work. It would be wonderful to hear a bit more, so we can “reach toward” your themes and feel their context.

Alexandra Volodina: I primarily work with theories of environment and experience—sensitivity—both in a broad philosophical sense and in more applied contexts. I’m particularly interested in embodiment, disability, vulnerability, and different ways of interacting with the world. I explore how new lines of perception, knowledge, and experience emerge—and how art can become a space for those lines to appear. That’s really the core of my current focus.

Hanna Zubkova: In my own educational practice, I also turn to the concepts of figure and ground. For me, they’re a way to explain how artistic thinking operates. It’s connected to reflection and to working with context—often with the documentary aspect.

Perhaps an artwork is inseparable from the story of how it came into being. That story, too, is a form of communication—a kind of affordance: it provides auxiliary possibilities for the viewer to interact with the work.

The works in this exhibition are interesting to me precisely because they combine visual clarity, rigor, and conciseness—with the potential to surface meanings, to make them manifest. And maybe this is where affordance is revealed: as a narrative that accompanies—but also generates—a particular environment, from which the figure of the work can emerge for the Other.

I suppose this is a good moment to transition to our next speaker, and to the broader question of the possibility of communication itself: is it needed? how does it emerge? how can it exist at all?

From what I understood while listening to today’s conversation, this question was being asked from within—how the object, the environment, and the narrative relate to one another, and how a kind of community forms around those relationships.

Anastasia Khaustova: What I want to share is quite spontaneous, but also deeply personal—an observation about what’s unfolding here.

When Hanna and I spoke about the possibility of me joining this conversation, I looked at some of the materials—but quickly realized that research-based practices demand serious, thoughtful engagement, including with the texts. And I have to say with some regret—speaking for myself—that I often don’t have enough time for that, even though I rarely go to exhibitions.

So I allowed myself to simply trust the flow—not to plan everything in advance, but to try to be in the process. To arrive with an open attentiveness, to be present, and to allow something to resonate.

If I had to name what felt most meaningful to me here, I’d say it’s the theme of translation. As someone who works with text, I’m very sensitive to the link between language and artwork. I often return to Salomé Voegelin’s piece Letter: Sonic Fictions, where she writes that literature can be a participant in an artwork—not a description or an interpretation, but a form of co-presence.

There’s a longing to be in immediate, undivided experience with a work of art. Without intermediaries. Without the need to explain, critique, or translate right away. Simply to be with the work—as it is.

And yet, I also understand that the very structure of this event sets up a framework: divisions of roles, hierarchies, and in the center—this cube around which we’re gathered like in front of Kubrick’s black monolith.

What I find interesting is whether it’s possible to step outside those roles. To meet not as artist and critic, curator and viewer—but simply as people sharing a mutual attentiveness, a shared vulnerability before the work.

Perhaps this is precisely the potential of such gatherings—to imagine a mixing, a blending of registers, forms of experience, and expressions. And specifically, a possibility of communication itself: as co-articulation, as translation, as an attempt to establish a different form of connection.

Now I’d like to try to express what particularly moved me in my direct encounter with the exhibition—and especially with Olesya Gumenenko’s work Narcissus Trap.

By the way, I counted eight mirrors—is there another one? I’ll look for it after (laughs). I actually like seeing myself in mirrors.

But here—I experienced a bug. I approached the mirrors… but didn’t see myself.

Instead, I saw reflections of other works, other viewers—but not my own.

And this produced an unexpectedly powerful effect on me.

Because it completely overturned the familiar situation, where I, let’s say, “narcissize” my experience—observe myself in the artwork, track my own perception, monitor how I appear through art. But here, it was different.

It wasn’t me being reflected in the mirror—it was the Other being reflected through my gaze. I became a kind of conduit for looking, not the center of the reflection.

And perhaps this is precisely the recursion that was mentioned at the beginning. And it truly works—physically, conceptually, intuitively.

I deeply value when an artistic experience becomes immediate—when it changes you in real time.

What we see in photographs, presentations, social media—that’s one thing.

But when you stand in front of a work, and it rethreads you—that’s what matters.

What moved me most just now was, I think, a moment of recognition. I realized that I’m surrounded by people I’ve encountered before—at various events, workshops, in college, in another life. And suddenly, all of that collapses into a single event, into a single space. This sense of multiple connections—threads that, for a brief span of time, are gathered into one shared moment—is very powerful. And I think I feel it physically: that even within this specific, performative, singular event, something collective is being lived.

And perhaps what interests me most in art—especially when we talk about art criticism—is its ability to create community.

Yes, the word community has become worn-out, maybe even devalued in places. But I don’t mean a social group—I mean a space of possibility. A platform where you can learn, interact, be.

Without slogans, without grandeur, without “hammers and slaps,” as the saying goes. Just—a space where it’s possible to be together in something shared.

That’s how I’ve always seen art: as a platform for possible modes of engagement with the future.

Which is why I felt especially close to the work Soft Diagram—a piece whose title literally includes the word future. It speaks directly to that.

In the end, this exhibition brought together everything that matters to me: perception, the emergence of the new, the possibility of communication. And what’s most important is that it didn’t happen on the level of language—not in formulations, not in intentions, not in concepts—but on the performative level.

Hanna Zubkova: It’s very moving to hear that things resonated—things we were indeed thinking about—yet seen through your fresh perspective.

One of the seminars in the workshop is titled: The Author Meant Nothing.

Because it’s not about the work necessarily having to express something, or the artist “successfully conveying” a message. No. It’s more like a composition—of directions, intuitions, backgrounds, scattered thoughts and gestures. And these figures—in the broadest sense—come together in space.

Not without the help of the curator.

And in this moment I’ve really seen just how essential that curatorial work is.

Because it’s the curator who starts to form these connections—not on paper, but in space.

It’s subtle and deeply thoughtful work.

Thank you, Liza, for that.

A huge thank you to the artists—for their attentiveness, for their precision, for making what they made. And I don’t want us to forget that this exhibition ultimately grew out of an educational process within the atelier, where participants gradually began to see themselves as independent artists and to relate consciously to what they choose to present.

From my perspective, this exhibition truly became what we hoped it would: a space where you don’t just see artworks, but experience something alongside them. It became an experience, not just a collection of objects.

Thank you so much to our guests, who helped us unfold all of this.

Who helped us hear it from the outside.

That was incredibly valuable.